Moral points apart, must you be trustworthy when requested how sure you’re about some perception? After all, it relies upon. On this weblog put up, you’ll be taught on what.

- Alternative ways of evaluating probabilistic predictions include dramatically completely different levels of “optimum honesty”.

- Maybe surprisingly, the linear operate that assigns +1 to true and totally assured statements, 0 to admitted ignorance and -1 to incorrect however totally assured statements incentivizes exaggerated, dishonest boldness. When you price forecasts that approach, you’ll be surrounded by self-important fools and endure from badly calibrated machine forecasts.

- If you need individuals (or machines) to present their really unbiased and trustworthy evaluation, your scoring operate ought to penalize assured however incorrect convictions extra strongly than it rewards assured right ones.

A probabilistic quiz recreation

David Spiegelhalter’s new (as of 2025) incredible e-book, “The Artwork of Uncertainty” – a must-read for everybody who offers with chances and their communication – includes a quick part on scoring guidelines. Spiegelhalter walks the reader via the quadratic scoring rule, and briefly mentions {that a} linear scoring rule will result in dishonest habits. I elaborate on that fascinating level on this weblog put up.

Let’s set the stage: Similar to in so many different eventualities and paradoxes, you end up in a TV present (sure, what an old style strategy to begin). You might have the chance to reply questions on frequent information and win some money. You might be requested sure/no-questions which might be expressed in a binary vogue, equivalent to: Is the world of France bigger than the world of Spain? Was Marie Curie born sooner than Albert Einstein? Is Montreal’s inhabitants bigger than Kyoto’s?

Relying in your background, these questions could be apparent for you, or they could be tough. In any case, you should have a subjective “greatest guess” in thoughts, and some extent of certainty. For instance, I really feel snug answering the primary, barely much less for the second, and I already forgot the reply to the third, although I regarded it as much as construct the instance. You would possibly expertise an analogous degree of confidence, or a really completely different one. Levels of certainty are, after all, subjective.

The twist of the quiz: You aren’t supposed to present a binary sure/no-answer as in a multiple-choice check, however to truthfully talk your diploma of conviction, that’s, to provide the likelihood that you simply personally assign to the true reply being “sure”. The quantity 0 then means “undoubtedly not”, 1 expresses “undoubtedly sure”, and 0.5 displays the diploma of uncertainty similar to the toss of a good coin — you then have completely no thought. Let’s name P(A) your true subjective conviction that assertion A is true. That likelihood can take any worth between 0 and 1, whereas A is sure to be both 0 or 1. You may then talk that quantity, however you don’t must, so we’ll name Q(A) the likelihood that you simply ultimately categorical in that quiz.

Normally, not each probabilistic expression Q is met with the identical pleasure, as a result of people typically dislike uncertainty. We’re a lot happier with the skilled that provides us “99.99%” or “0.01%” chances for one thing to be or to not be the case, and we favor them significantly over the specialists producing “25%” and “75%” maybe-ish assessments. From a rational perspective, extra informative chances (“sharp predictions”, near 0 or near 1) are favorable over uninformative ones (“unsharp predictions”, near 0.5). Nevertheless, a modest however truthful prediction continues to be price greater than a daring however unreliable one that might make you go all-in. We must always due to this fact be sure that individuals don’t lie about their diploma of conviction, so that actually 99% of the “99%-sure” predictions are literally true, 12% or the “12%-sure”, and so forth. How can the quiz grasp be sure that?

The Linear Scoring Rule

Probably the most simple approach that one would possibly provide you with to guage probabilistic statements is to make use of a linear scoring rule: In the perfect case, you’re very assured and proper, which suggests Q(A)=P(A)=1 and A is true, or Q(A)=P(A)=0 and A is fake. We then add the rating +1=r(Q=1, A=1)=r(Q=0, A=0) to the steadiness. Within the worst case, you had been very positive of your self, however incorrect; that’s, Q(A)=P(A)=1 whereas A is fake, or Q(A)=P(A)=0 whereas A is true. In that unlucky case, we subtract –1=r(Q=1, A=0)=r(Q=0, A=1) from the rating. Between these excessive circumstances, we draw a straight line. Once you categorical maximal uncertainty by way of Q(A)=0.5, now we have 0=r(Q=0.5, A=1)=r(Q=0.5, A=0), and neither add nor subtract something.

The practical type of this linear reward operate isn’t significantly spectacular, however its visualization will come helpful within the following:

No shock right here: If A is true, the perfect factor you can have completed is to speak “Q=1”, if A is fake, the perfect technique would have been to provide “Q=0”. That’s what’s visualized by the black dots: They level to the biggest worth that the reward operate can attain for the actual worth of the reality. That’s a superb begin.

However you usually do not know with absolute certainty whether or not the reply is “sure, A is true” or “no, A is fake”, you solely have a subjective intestine feeling. So what must you do? Do you have to simply be trustworthy and talk your true perception, e.g. P=0.7 or P=0.1?

Let’s set ethics apart, and contemplate the reward that we wish to maximize. It then seems that you simply shouldn’t be trustworthy. When evaluated by way of the linear scoring rule, it is best to lie, and talk Q(A)=0 when P(A)(A)=1 when P(A)>0.5.

To see this shocking end result, let’s compute the expectation worth of the reward operate, assuming that your perception is, on common, right (cognitive psychology teaches us that that is an unrealistically optimistic assumption within the first place, we’ll come again to that beneath). That’s, we assume that in about 70% of the circumstances while you say P=0.7, the true reply is “sure, A is true”, in about 75% of the circumstances while you say P=0.25, the true reply is “no, A is fake”. The anticipated reward R(P, Q) is then a operate of each the trustworthy subjective likelihood P and of the communicated likelihood Q, specifically the weighted sum of the reward r(Q, A=1) and r(Q, A=0):

R(P, Q) = P * r(Q, A=1) + (1-P) * r(Q, A=0)

Right here come the ensuing R(P,Q) for 4 completely different values of the trustworthy subjective likelihood P:

The maximally attainable reward on the long run isn’t at all times 1 anymore, nevertheless it’s bounded by 2|P-0.5| — ignorance comes at a value. Clearly, the perfect technique is to confidently talk Q=1 so long as P>0.5, and to speak an equally assured Q=0 when Psee the place the black dots lie within the determine.

Underneath a linear scoring rule, when it’s extra seemingly than not that the occasion happens — faux you’re completely sure that it’s going to happen. When it’s marginally extra seemingly that it doesn’t happen — be daring and proclaim “that may by no means occur”. You may be incorrect generally, however, on common, it’s extra worthwhile to be daring than to be trustworthy.

Even worse: What occurs when you’ve completely no clue, no thought concerning the final result, and your subjective perception is P=0.5? Then you may play secure and talk that, or you may take the possibility and talk Q=1 or Q=0 — the expectation worth is similar.

If discover this a disturbing end result: A linear reward operate makes individuals go all-in! There isn’t any approach as forecast client to tell apart a slight tendency of 51% from a “fairly seemingly” conviction of 95% or from an almost-certain 99.9999999%. In that quiz, the good gamers will at all times go all-in.

Worse, many conditions in life reward unsupported confidence greater than considerate and cautious assessments. Cautiously stated, not many individuals are being closely sanctioned for making clearly exaggerated claims…

A quiz present is one factor, however, clearly, it’s fairly an issue when individuals (or machines…) are pushed to not talk their true diploma of conviction on the subject of estimating the chance of great and dramatic occasions equivalent to earthquakes, conflict and catastrophes.

How can we make them to be trustworthy (within the case of individuals) or calibrated (within the case of machines)?

Punishing assured wrongness: The Quadratic Scoring Rule

If the likelihood for one thing to occur is estimated to be P=55% by some skilled, I need that skilled to speak Q=55%, and never Q=100%. For chances to have any worth for our selections, they need to replicate the true degree of conviction, and never an opportunistically optimized worth.

This cheap ask has been formalized by statisticians by correct scoring guidelines: A correct scoring rule is one which incentivizes the forecaster to speak their true diploma of conviction, it’s maximized when the communicated chances are calibrated, i.e. when predicted occasions are realized with the anticipated frequency. At first, the query would possibly come up whether or not such a scoring rule can exist in any respect. Fortunately, it may well!

One correct scoring rule is the quadratic scoring rule, also called the Brier rating. For excessive communicated chances (Q=1, Q=0), the values are the exact same as for the linear scoring rule, however we don’t draw straight line between these, however a parabola. By doing that, we reward trustworthy ignorance: +0.5 is awarded for a communicated likelihood of Q=0.5.

This reward operate is uneven: Once you enhance your confidence from Q=0.95 to Q=0.98 (and A is true), the reward operate solely will increase marginally. Then again, when A is fake, that very same enhance of confidence leaning in direction of the incorrect final result is pushing down the reward significantly. Clearly, the quadratic reward thereby nudges one to be extra cautious than the linear reward. However will it suffice to make individuals trustworthy?

To see that, let’s compute the expectation worth of the quadratic reward as a operate of each the true trustworthy likelihood P and the communicated one Q, identical to we did within the linear case:

R(P, Q) = P * r(Q, A=1) + (1-P) * r(Q, A=0)

The ensuing anticipated reward, for various values of the trustworthy likelihood P, is proven within the subsequent determine:

Now, the maxima of the curves lie precisely on the level for which Q=P, which makes the proper technique speaking truthfully one’s personal likelihood P. Each exaggerated confidence and extreme warning are penalized. After all, by understanding extra within the first place, you’ll be capable to make sharper and extra assured statements (extra predictions Q=P which might be both near 1 or near 0). However trustworthy ignorance is now rewarded with +0.5. Higher be secure than sorry.

What can we be taught from that? The reward that’s maximized by truthfully communicated chances sanctions “surprises” (QQ>0.5 and the occasion is definitely false) fairly strongly. You lose extra when you find yourself incorrect together with your tendency (Q>0.5 or Q

Logarithmic reward

The quadratic reward operate isn’t the one one which rewards honesty (there are infinitely many correct scoring guidelines): The logarithmic reward penalizes being confidently incorrect (P=0, however reality is “sure, A is true”; P=1, but reality is “no, A is fake”) with an unassailable -infinity: The rating is solely the logarithm of the likelihood that had been predicted for the occasion that ultimately occurred — the plot is minimize off on the y-axis for that motive:

The logarithmic reward breaks the symmetry between “having communicated a barely too-high” and “having expressed a barely too-low” likelihood: In direction of uninformative Q=0.5, the penalty is weaker than in direction of informative Q=0 or Q=1, which we see within the expectation values:

The logarithmic scoring rule closely penalizes the project of a likelihood of 0 to one thing that then very surprisingly occurred: Any individual who has to confess “I actually although it was completely unattainable” after the truth that they assigned Q=0 received’t be invited to supply predictions ever once more…

Incentivizing sandbagging: The Cubic Scoring Rule

Scoring guidelines can push forecasters to be over-confident (see the linear scoring rule), they are often correct (see the quadratic and logarithmic scoring guidelines), however they’ll additionally punish “being boldly incorrect” so completely that forecasters would somewhat faux they don’t know actually even when they do. A cubic scoring rule would result in such extreme warning:

The expectation values of the reward now make individuals somewhat talk values which might be much less informative (nearer to 0.5) than their true convictions: As an alternative of an trustworthy Q=P=0.2, the optimum is at Q=0.333, as a substitute of trustworthy Q=P=0.4, the optimum is Q=0.4495.

In different phrases, to be supplied trustworthy judgements, don’t exaggerate the punishment of sturdy however ultimately incorrect convictions both — in any other case you’ll be surrounded by indecisive and hesitant cowards…

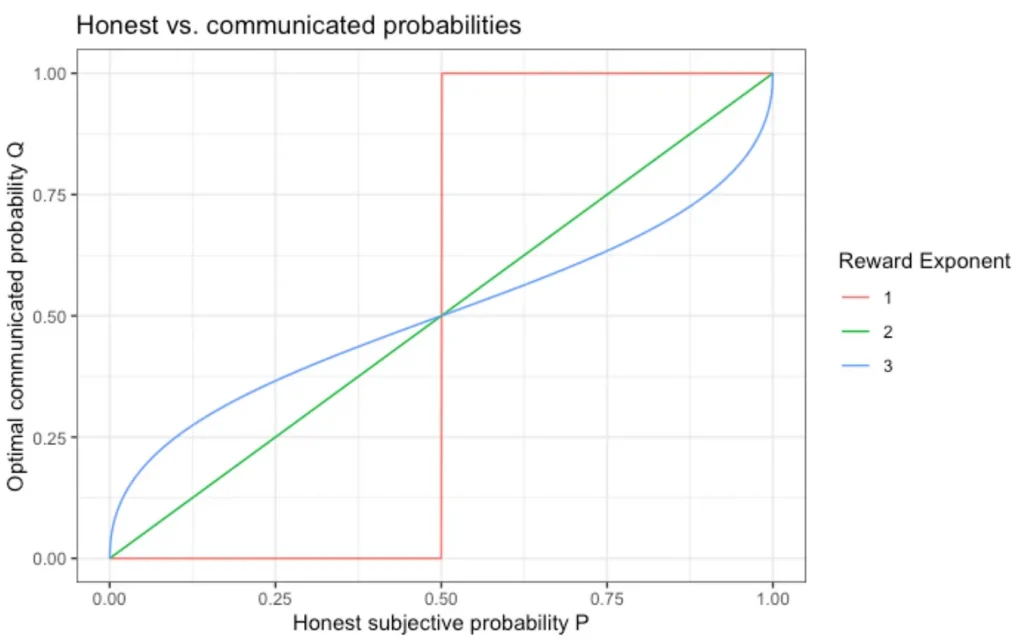

Sincere and communicated chances

The next plot recapitulates the argument by displaying the optimum communicated likelihood Q as a operate of the true perception P. For a linear reward (Exponent 1), you’ll both talk Q=0 or Q=1, and never disclose any details about your true diploma of conviction. The quadratic reward (Exponent 2) makes you be trustworthy (Q=P), whereas the cubic reward (Exponent 3) helps you to set overly cautious Q values.

In actuality, our decisions are sometimes binary, and, relying on the “false constructive” and “false detrimental” price and the “true constructive” and “true detrimental” reward, we’ll set the brink on our subjective likelihood to take or not take a sure motion to completely different values. It isn’t in any respect irrational to plan completely for a likelihood P=0.01=1% disaster.

If chances are subjective, how can they be “incorrect”?

Scoring guidelines have two primary purposes: On a technical degree, when coaching a probabilistic statistical or machine studying mannequin on knowledge, optimizing a correct scoring rule will yield calibrated and as-sharp-as-possible probabilistic forecasts. In a extra casual setting, when a number of specialists estimate the likelihood for one thing (usually dramatic) to occur, one desires to ensure that the specialists are trustworthy and don’t attempt to overplay or downplay their subjective uncertainty (watch out for group dynamics!). Tremendous-forecasters certainly use quadratic scoring guidelines to assist replicate on their diploma of confidence and to coach themselves to grow to be extra calibrated.

Again to our preliminary quiz recreation. Earlier than answering, it is best to undoubtedly ask how you’re evaluated. The analysis process does matter, even if you’re advised it doesn’t. Equally, when you find yourself given a multiple-choice-test, make sure to perceive whether or not it could be worthwhile to verify a field even if you’re solely very marginally sure about its correctness.

However how can a quiz involving subjective chances be evaluated in any respect in an goal vogue? In accordance with Bruno De Finetti, “likelihood doesn’t exist”, so how can we then choose the possibilities that individuals categorical? We don’t choose individuals’s style both! David Spiegelhalter emphasizes in “The Artwork of Uncertainty” that uncertainty isn’t “a property of the world, however of our relationship with the world”.

Nevertheless, subjective doesn’t imply unfalsifiable.

I could be 99% positive that France is bigger than Spain, 75% positive that Marie Curie was born earlier than Albert Einstein, and 55% positive that Montreal is bigger than Kyoto. The numbers that you assign to those statements will most likely (pun meant) be completely different. Your relationship to the world is a special one than mine. That’s OK.

We will be each proper within the sense that we categorical calibrated chances, even when we assign completely different chances to the identical occasions.

A extra commonplace setting: After I enter a grocery store, I can assign fairly informative (fairly excessive or fairly low) chances to me shopping for sure merchandise — I usually know properly what I intend to buy. The information scientist working on the grocery store doesn’t know my private procuring checklist, even after having collected appreciable private knowledge. The likelihood that they assign to me shopping for a bottle of orange juice shall be fairly completely different from the one which I assign to me doing that — each chances will be “right” within the sense that they’re calibrated on the long run.

Subjectivity doesn’t imply arbitrariness: We will combination predictions and outcomes, and consider to which extent the predictions are calibrated. Scoring guidelines assist us exactly with that process, as a result of they concurrently grade honesty and data: Every forecaster will be evaluated individually upon their predicted chances. The one that’s most knowledgeable (producing close-to-1 and close-to-0 chances) whereas being trustworthy on the identical time will win the quiz. Completely different scoring guidelines can then rank strong-but-slightly-uncalibrated towards weaker-but-calibrated predictions in a different way.

As talked about above, honesty and calibration usually are not equal in observe. We would really imagine 100 instances that sure occasions ought to happen in 20% of every case — however the true variety of occurrences would possibly considerably differ from 20. We could be trustworthy about our perception and categorical P=Q, however that perception itself is often uncalibrated! Kahneman and Tversky have studied the cognitive biases that usually make extra assured than we ought to be. In a approach, we frequently behave as if a linear scoring rule judged our predictions, making us lean in direction of the daring facet.

Source link